Peace officers, including sheriffs, take an oath to uphold the Constitution—but when they exceed their lawful authority, they operate under color of law. Even without malicious intent, incompetence or inadequate training can result in serious civil rights violations. Under 18 U.S.C. § 242, depriving someone of their rights—whether knowingly or through ignorance—is a federal offense. The law is clear: ignorance is no excuse, especially for those entrusted to enforce it.

Peace officers—including sheriffs, deputies, and police—are entrusted with an important duty: to uphold and defend the Constitution. Their authority is delegated by the people, meaning they only have as much lawful power as the people themselves can give. They swear an oath of office to protect rights, not override them.

But what happens when they go beyond those limits? What if a sheriff unlawfully detains, harasses, or uses force against someone who is not under their jurisdiction or who is peacefully exercising a constitutional right?

That’s where the concept of color of law comes in—and it’s serious.

🔹 The Duty of a Peace Officer

Every sheriff, deputy, and public servant in law enforcement is bound by a constitutional oath. This oath requires them to:

-

Uphold the U.S. Constitution and the constitution of their state

-

Protect the natural and civil rights of all individuals

-

Operate within the limits of their lawful jurisdiction

-

Respect due process, freedom of movement, speech, religion, and other inalienable rights

In essence, they are public servants—not rulers—and their power exists to serve, not control.

🔹 What Is Delegated Authority?

Delegated authority is lawful power temporarily given to an officer by the people, through law. That power must be:

-

Used only for constitutional purposes

-

Applied only within jurisdiction (e.g., counties or districts)

-

Limited by due process and equal protection under the law

A peace officer has no inherent authority over a man or woman unless there’s a lawful cause—such as probable cause of a crime, a valid warrant, or an immediate threat to public safety.

🔺 When They Cross the Line

If a sheriff or peace officer:

-

Stops or detains someone without probable cause

-

Harasses a non-citizen national or someone not subject to statutory jurisdiction

-

Interferes with constitutionally protected activities (like travel, speech, or lawful protest)

-

Enforces statutes as if they were superior to rights

…they are no longer acting lawfully. Instead, they’re using the appearance of authority to commit an act that violates rights.

This is called acting under color of law.

⚖️ What Is “Color of Law”?

Color of law means someone pretends to be acting lawfully, using their badge or title, but is actually violating the law.

📘 18 U.S.C. § 242 defines it as:

“The willful deprivation of rights under color of any law, statute, ordinance, regulation, or custom.”

This is a federal crime and a civil rights violation. The law applies to any official—including sheriffs—who uses their position to intimidate, coerce, assault, detain, or punish someone unlawfully.

Importantly, color of law doesn’t require malicious intent. A public official can be guilty of acting under color of law simply by being ignorant, poorly trained, or negligent in their understanding of the Constitution and legal boundaries. A sheriff who misapplies the law, or who follows unconstitutional procedures passed down through flawed training, may believe they are acting properly—but if they violate someone’s rights, they are still acting under color of law.

⚖️ Legal Maxim: “Ignorantia juris non excusat” — Ignorance of the law excuses no one.

This maxim applies equally to the people and to public servants. When a peace officer deprives someone of rights—whether through incompetence, misunderstanding, or arrogance—they are liable for their actions. Incompetence is not immunity. Lack of training is not an excuse. The duty to know and uphold the law is part of the oath they swear.

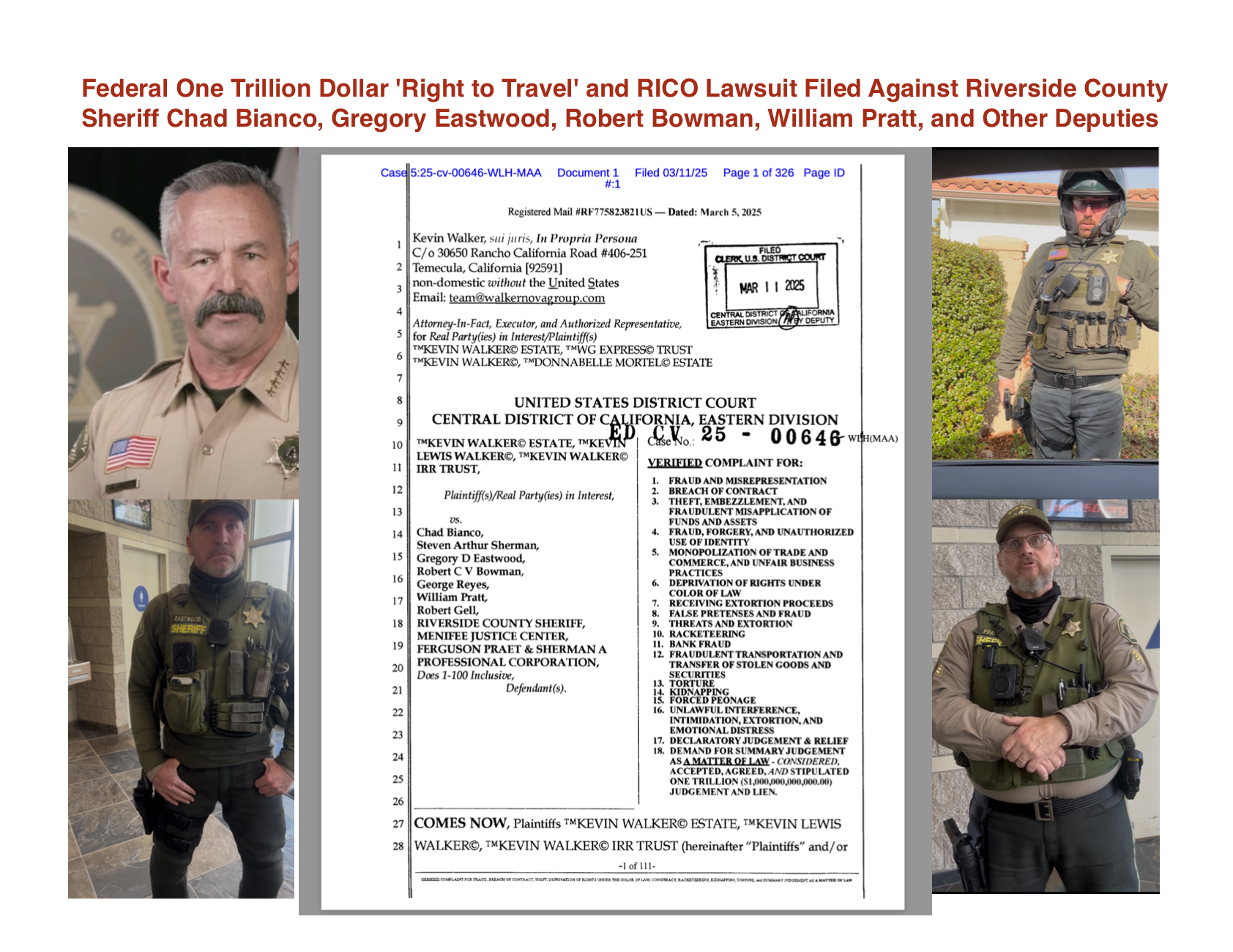

🔹 Example: Harassment of a Non-Citizen National

Let’s say a man identifies as a non-citizen national, traveling freely in his private automobile. He is not engaged in commerce and poses no threat to anyone. A sheriff, acting outside his jurisdiction, pulls him over without probable cause, demands ID, and threatens arrest.

This sheriff is not enforcing the law—he is violating the constitutional right to travel, acting outside his jurisdiction, and operating under color of law.

📜 Remedies for Victims

When someone is harmed under color of law, they have powerful legal tools available:

Civil Remedies:

-

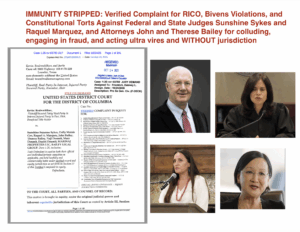

42 U.S.C. § 1983 – Civil action for deprivation of rights

-

Bivens claim – Lawsuit against federal agents violating rights

Criminal Violations:

-

18 U.S.C. § 241 – Conspiracy against rights

-

18 U.S.C. § 242 – Deprivation of rights under color of law

Peace officers who violate these laws can face:

-

Civil lawsuits

-

Loss of qualified immunity

-

Criminal charges

-

Loss of office or certification

🧠 Final Thought: Know the Boundaries

Law enforcement officers are not above the law. They are bound by it, just like everyone else. When sheriffs or any public servants exceed their delegated authority and violate the rights of the people, they step into dangerous legal territory.

Understanding where authority ends and where rights begin is key—not just for the people, but for the peace officers themselves.

Because the badge is not a license to violate the Constitution.