“Pro Se” denotes voluntarily representing oneself within the court’s jurisdiction, thereby consenting to its authority and procedures. In contrast, “Pro Per” allows individuals to assert their personal status and directly challenge the court’s jurisdiction, avoiding representation as a legal fiction. This distinction underscores the significance of an Affidavit of Power of Attorney In Fact, which empowers an Attorney In Fact to represent a trust without requiring a licensed attorney in the public jurisdiction. Understanding these legal roles is crucial in navigating court standing and asserting constitutional and contractual rights effectively.

Attorney At Law (Public Jurisdiction)

- Definition: A licensed member of a state bar authorized to practice law within a specific jurisdiction.

- Public Role: Functions as an officer of the court, bound by statutory rules and professional ethics.

- Representation: Authorized to represent individuals, entities, and trusts in legal proceedings.

- Court Standing: Granted formal authority to file appearances and argue cases in court.

Attorney In Fact (Private Jurisdiction)

- Definition: A person granted authority through a contractual Affidavit: Power of Attorney In Fact to act on behalf of another, including trusts.

- Private Role: Not required to be a licensed attorney; authority derives solely from the affidavit’s terms.

- Scope of Authority: Can be broad (general authority) or limited to specific actions (special authority).

- Court Representation: May represent a trust in legal actions if the affidavit explicitly authorizes such representation.

Pro Se vs. Pro Per: Jurisdictional and Expectational Differences

Pro Se (On One’s Own Behalf)

- Typically implies voluntary entry into the court’s jurisdiction without challenging presumptions.

- A pro se litigant essentially consents to the jurisdiction and procedures of the court by choosing to represent themselves.

Pro Per (In Propria Persona)

- Asserts the litigant’s direct personal status, avoiding representation as a legal fiction and often invoking sovereignty over jurisdictional matters.

- Pro per litigants may retain their sovereign status and challenge the court’s jurisdiction over them, not voluntarily submitting to jurisdiction as a pro se litigant would.

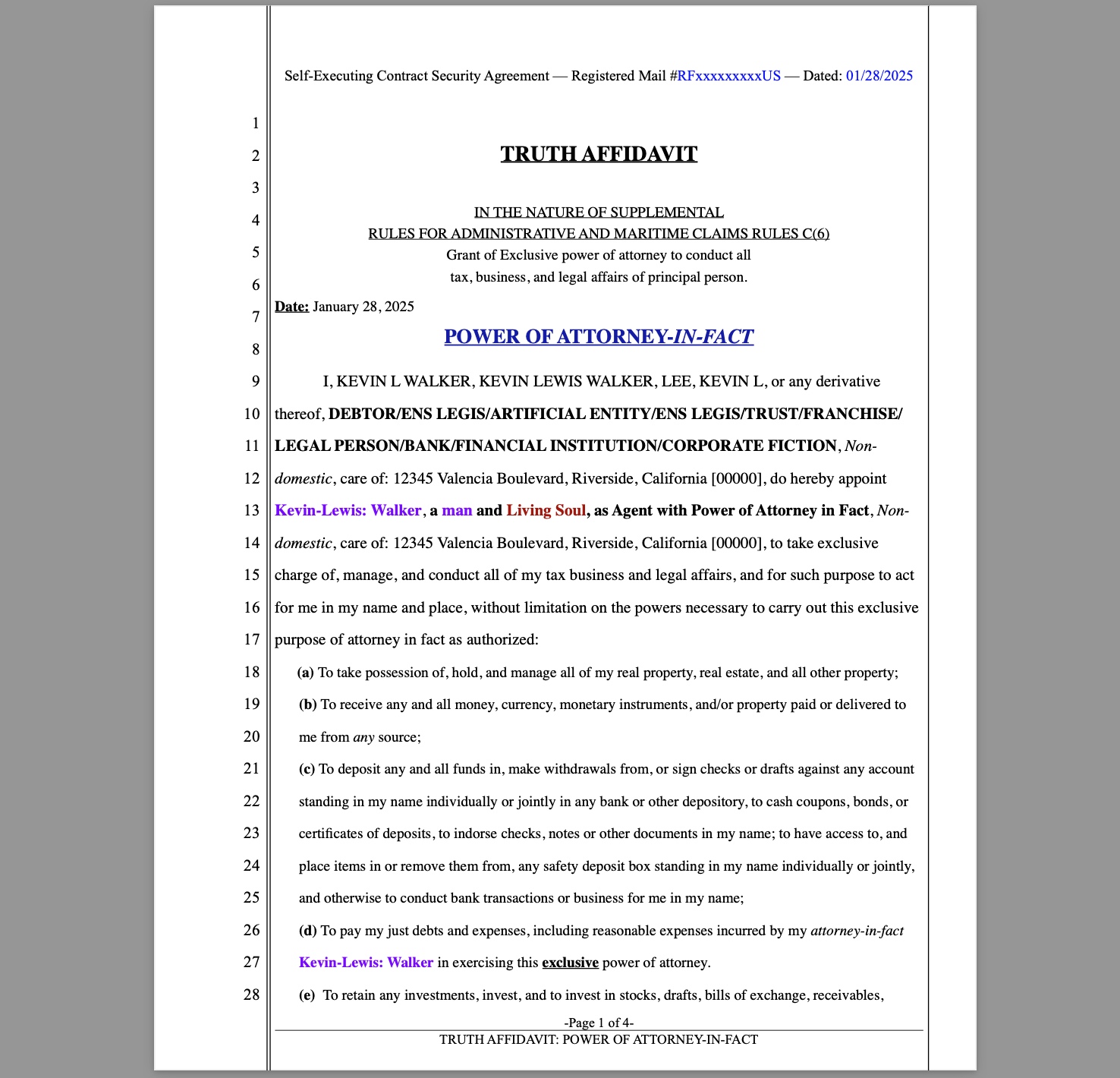

How an Attorney In Fact Can Represent a Trust in Legal Matters

Affidavit: Power of Attorney In Fact

To establish legal standing in court, an Attorney In Fact should present:

- Sworn Affidavit: Attesting to their authority under the Affidavit: Power of Attorney In Fact.

- Proof of Authority: The original or certified copy of the notarized and properly executed affidavit.

Representation “In Propria Persona”

- Trusts and corporations are traditionally considered artificial persons and must appear through an “Attorney At Law” (Osborn v. Bank of U.S., 22 U.S. 738 (1824)).

- However, courts must recognize an Attorney In Fact representing a trust “In Propria Persona” when constitutional and contractual rights are asserted.

Affidavit of Power of Attorney In Fact in Trust Representation

An affidavit of Power of Attorney In Fact grants authority to an Attorney In Fact to act on behalf of the trust in legal matters. It serves several essential functions:

- Grants Representation: Authorizes the Attorney In Fact to represent the trust and make decisions within the scope defined in the affidavit.

- Establishes Legal Standing: Provides proof of the Attorney In Fact’s authority to act on behalf of the trust, allowing engagement in legal actions.

- Defines Scope of Authority: Clearly outlines the powers granted to the Attorney In Fact, ensuring they act within authorized capacity.

In court, the affidavit is used to demonstrate the Attorney In Fact’s legal authority to represent the trust.

Key Legal Precedents

- Article I, Section 10 of the U.S. Constitution:

Prohibits states from impairing contractual obligations, including an Affidavit: Power of Attorney In Fact.“No State shall… pass any Law impairing the Obligation of Contracts.”

- Hale v. Henkel, 201 U.S. 43 (1906):

Establishes that the right to contract is unlimited except as restricted by law.“The individual may stand upon his constitutional rights as a citizen. He is entitled to carry on his private business in his own way… His rights are such as existed by the law of the land [Common Law] long antecedent to the organization of the State and can only be taken from him by due process of law.”

- Miller v. U.S., 230 F.2d 486 (1956):

“The claim and exercise of a constitutional right cannot be converted into a crime.”

- Miranda v. Arizona, 384 U.S. (1966):

“Where rights secured by the Constitution are involved, there can be no rule-making or legislation which would abrogate them.”

- Marbury v. Madison, 5 U.S. (1 Cranch) 137, 177 (1803):

“A law repugnant to the Constitution is void.”

- Norton v. Shelby County, 118 U.S. 425, 442 (1886):

“An unconstitutional act is not law; it confers no rights; it imposes no duties; it creates no office; it is, in legal contemplation, as inoperative as though it had never been passed.”

- Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U.S. 356 (1886):

“Sovereignty itself remains with the people, by whom and for whom all government exists and acts.”

Overcoming Barriers to Court Recognition

Courts have historically resisted allowing what they arrogantly dismiss as “non-attorneys” to represent trusts or entities. However, an Attorney In Fact can assert their standing by presenting:

- Comprehensive Affidavit: Clearly authorizing litigation and legal representation on behalf of the trust.

- Documented Affidavits: Filing notarized affidavits attesting to the validity and scope of the Affidavit: Power of Attorney In Fact.

- Constitutional Rights: Citing Article I, Section 10 and Hale v. Henkel as legal precedents.

- Jurisdictional Clauses: Reserving all rights under UCC 1-308 to protect against procedural dismissals.