What Are Bare Criminal Statutes?

Bare criminal statutes define behaviors deemed unlawful and prescribe penalties such as fines, imprisonment, or both. These statutes are designed to serve as societal deterrents and ensure public safety and order. However, they do not inherently grant private individuals the right to file lawsuits.

Examples of Bare Criminal Statutes:

- Mail Fraud (18 U.S.C. § 1341): Criminalizes schemes to defraud through the postal system but does not provide a private right of action.

- Conspiracy Against Rights (18 U.S.C. § 241): Penalizes conspiracies to infringe upon constitutional rights but requires prosecution by government authorities.

Key Features of Bare Criminal Statutes

- Exclusive Enforcement by Governmental Authorities

Only government officials, such as attorneys general, district attorneys, or U.S. attorneys, can prosecute crimes under these statutes. Their role is to act on behalf of the public to hold offenders accountable for their actions. - No Automatic Private Remedy

Criminal statutes do not inherently allow individuals to seek civil remedies. A private right of action must be explicitly stated or implied by the statute, or individuals must rely on other laws to bring their claims.

What Is a Private Right of Action?

A private right of action enables individuals to file lawsuits in civil court to enforce statutory rights or seek remedies for harm. This right can be explicitly provided by a statute or, in rare cases, implied by judicial interpretation.

Explicit Private Rights of Action:

- Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964: Enables employees to sue employers for workplace discrimination.

- Fair Debt Collection Practices Act (FDCPA): Permits consumers to sue debt collectors for statutory violations.

Implied Private Rights of Action:

Courts may infer a private right of action under a statute even if it is not explicitly provided. The U.S. Supreme Court outlined four factors in Cort v. Ash (422 U.S. 66, 1975) to determine whether such a right exists:

- The plaintiff must belong to the class the statute seeks to protect.

- Legislative intent to create or deny such a remedy must be evident.

- The remedy must align with the statute’s purpose.

- The cause of action should not traditionally belong solely to state law.

Limitations on Private Enforcement of Criminal Statutes

1. Private Citizens Cannot Prosecute Criminal Offenses

Criminal law enforcement is reserved for public officials to prevent misuse of the legal system and maintain prosecutorial discretion.

2. Judicial Rulings on Private Claims

Courts routinely dismiss lawsuits based solely on criminal statutes unless a private right of action is clearly articulated. For instance, a plaintiff harmed by fraudulent activity cannot sue under 18 U.S.C. § 1341 (Mail Fraud) unless another statute grants a civil remedy.

Articulating a Private Right of Action

To succeed in court, plaintiffs must rely on statutes that explicitly or implicitly grant a private right of action. Without this, claims based solely on criminal statutes will likely be dismissed.

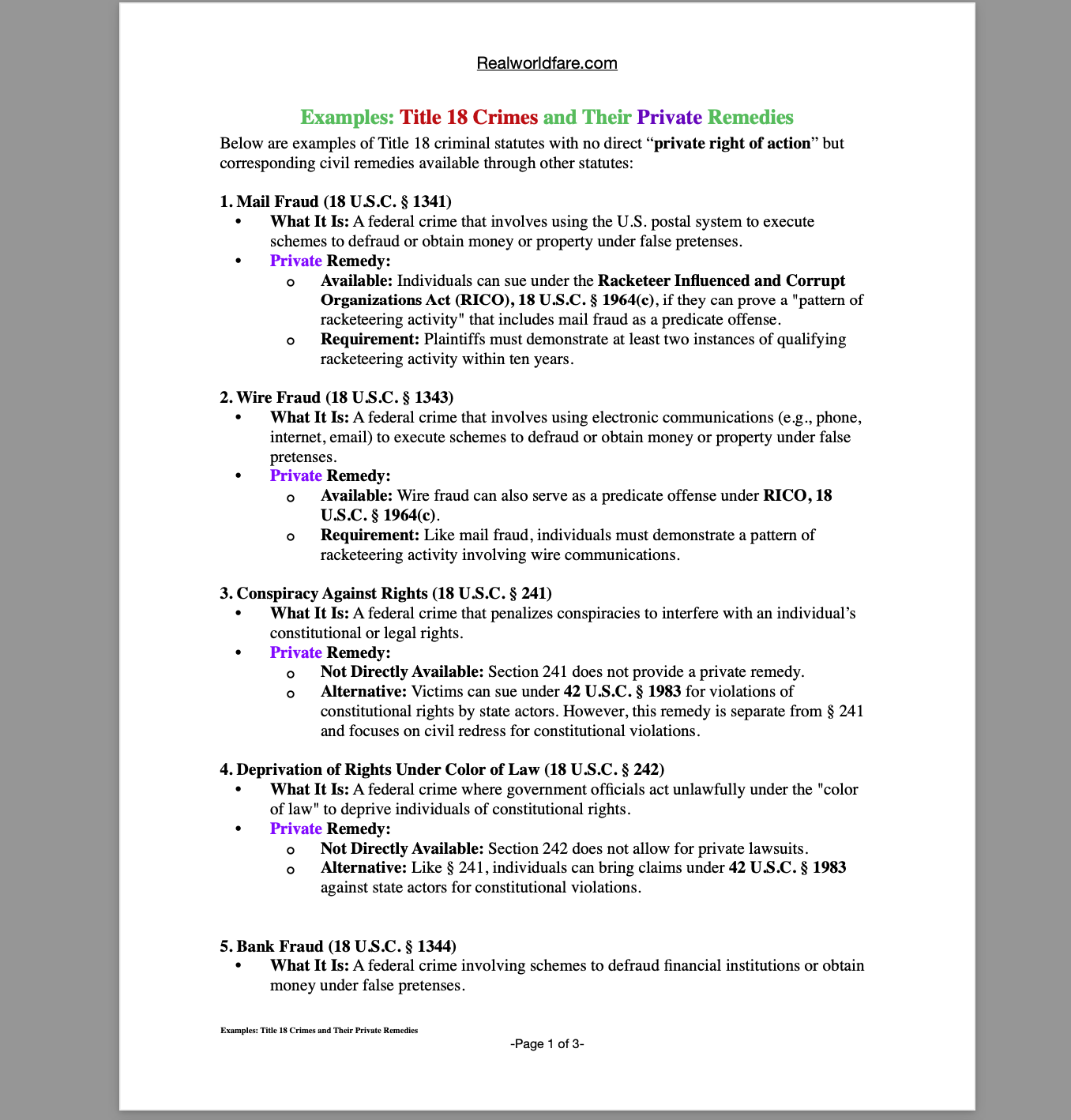

Examples: Title 18 Crimes and Their Private Remedies

Below are examples of Title 18 criminal statutes with no direct private right of action but corresponding civil remedies available through other statutes:

1. Mail Fraud (18 U.S.C. § 1341)

- What It Is: A federal crime that involves using the U.S. postal system to execute schemes to defraud or obtain money or property under false pretenses.

- Private Remedy:

- Available: Individuals can sue under the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act (RICO), 18 U.S.C. § 1964(c), if they can prove a “pattern of racketeering activity” that includes mail fraud as a predicate offense.

- Requirement: Plaintiffs must demonstrate at least two instances of qualifying racketeering activity within ten years.

2. Wire Fraud (18 U.S.C. § 1343)

- What It Is: A federal crime that involves using electronic communications (e.g., phone, internet, email) to execute schemes to defraud or obtain money or property under false pretenses.

- Private Remedy:

3. Conspiracy Against Rights (18 U.S.C. § 241)

- What It Is: A federal crime that penalizes conspiracies to interfere with an individual’s constitutional or legal rights.

- Private Remedy:

- Not Directly Available: Section 241 does not provide a private remedy.

- Alternative: Victims can sue under 42 U.S.C. § 1983 for violations of constitutional rights by state actors. However, this remedy is separate from § 241 and focuses on civil redress for constitutional violations.

4. Deprivation of Rights Under Color of Law (18 U.S.C. § 242)

- What It Is: A federal crime where government officials act unlawfully under the “color of law” to deprive individuals of constitutional rights.

- Private Remedy:

- Not Directly Available: Section 242 does not allow for private lawsuits.

- Alternative: Like § 241, individuals can bring claims under 42 U.S.C. § 1983 against state actors for constitutional violations.

5. Bank Fraud (18 U.S.C. § 1344)

- What It Is: A federal crime involving schemes to defraud financial institutions or obtain money under false pretenses.

- Private Remedy:

6. False Claims (18 U.S.C. § 287)

- What It Is: A federal crime that involves submitting false claims for payment to the federal government.

- Private Remedy:

- Available:

- Under the False Claims Act (FCA), 31 U.S.C. §§ 3729-3733, private individuals (whistleblowers) can file qui tam lawsuits on behalf of the government.

- Incentive: Successful whistleblowers can receive a percentage of the recovered funds.

- Available:

7. Identity Theft (18 U.S.C. § 1028)

- What It Is: A federal crime involving the misuse of another person’s identifying information (e.g., Social Security number, driver’s license).

- Private Remedy:

- Available in Limited Circumstances:

- Victims may sue under the Fair Credit Reporting Act (FCRA), 15 U.S.C. § 1681n, if identity theft involves harm related to credit reporting.

- Broader remedies depend on specific circumstances of harm caused by the theft.

- Available in Limited Circumstances:

8. Theft or Embezzlement from Employee Benefit Plans (18 U.S.C. § 664)

- What It Is: A federal crime involving theft, embezzlement, or misuse of funds from employee benefit plans.

- Private Remedy:

- Available:

- Under the Employee Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA), 29 U.S.C. § 1132(a), participants and beneficiaries can sue fiduciaries for breaches of duty, including embezzlement or mismanagement of plan funds.

- Available:

9. Human Trafficking (18 U.S.C. §§ 1581-1594)

- What It Is: A series of federal laws criminalizing forced labor, involuntary servitude, and human trafficking.

- Private Remedy:

- Available:

- Victims can sue traffickers under the Trafficking Victims Protection Act (TVPA), 18 U.S.C. § 1595, for damages.

- This is explicitly authorized by the statute.

- Available:

10. Monopolization of Trade and Commerce (15 U.S.C. § 2 & 18 U.S.C. § 1951)

- What It Is:

- 15 U.S.C. § 2: Prohibits monopolization, attempted monopolization, and conspiracies to monopolize trade or commerce.

- 18 U.S.C. § 1951 (Hobbs Act): Criminalizes extortion, including interference with commerce by threats or violence.

- Private Remedy:

- Available:

- Requirement: Plaintiffs must demonstrate harm to competition or commerce caused by the monopolistic behavior.

Final Notes:

- Many remedies depend on proving harm or meeting specific legal thresholds (e.g., intent, causation, damages).

- Criminal statutes themselves often do not provide private remedies, but other laws (like RICO, § 1983, or FCA) may allow for civil lawsuits based on the conduct described in these statutes