“Attorney at Law”: Licensed Legal Professional:

An “Attorney at Law” or “Lawyer” is a person who has met the legal qualifications to practice law. This typically involves completing law school, passing the bar exam, and being admitted to the bar association of a specific jurisdiction, which governs their professional conduct. “Attorneys at Law” are authorized to:

- Represent clients in legal matters, including court proceedings

- Draft legal documents such as contracts, wills, and litigation papers

- Provide “legal” advice and counsel to clients

- Negotiate “legal” agreements on behalf of their clients

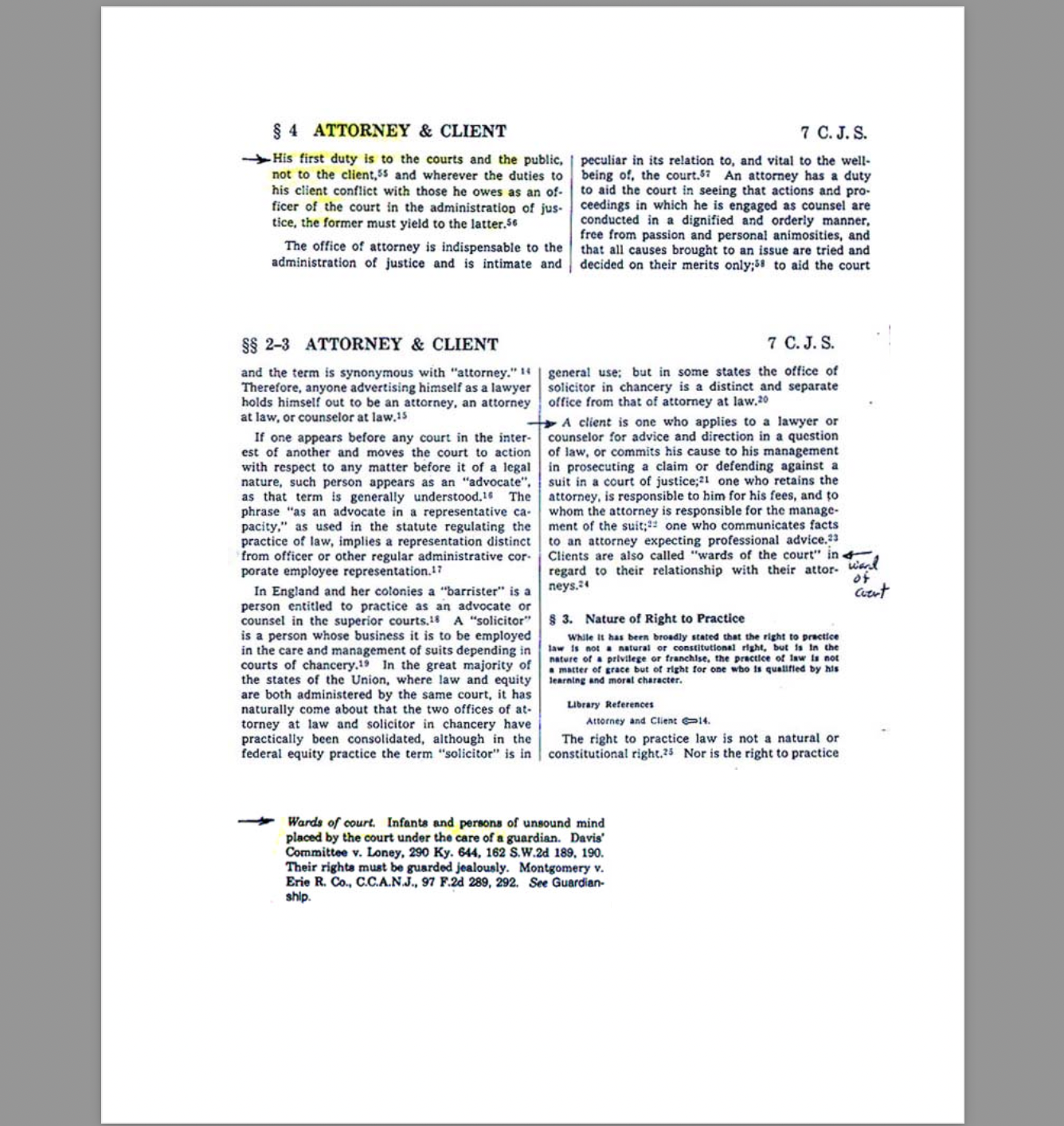

However, it’s important to note that “Lawyers” have a duty not just to their clients but also to the court. In fact, according to 4 ATTORNEY & CLIENT 7 C.J.S. and 2-3 ATTORNEY & CLIENT 7 C.J.S., a client represented by an “Attorney at Law” is considered a “ward of the court.” This means the “attorney” is obligated to place the interests of the court first, above even the interests of the client. The client is thus in a diminished position of authority over their own case once representation is retained.

Furthermore, becoming a “ward of the court“ grants the respective court or administrative tribunal jurisdiction over the individual. In this scenario, the living breathing man or woman/private citizen/national loses certain rights by way of contract—the retained “attorney” acts as the “handler” ushering the individual into the system, making them subject to colorable laws and potential deprivation under the color of law. They exchange their rights as a “private citizen/Sovereign” for benefits, as a “ward of the court,” by way their own willful contract with the “Attorney at Law” aka “Lawyer,” whom essentially is a double agent, owing their loyalty to the court.

Attorney in Fact: Appointed Representative:

An Attorney in Fact, on the other hand, is not necessarily a “Lawyer.” This role is typically created through a legal document such as a Power of Attorney, an Affidavit, or a Contract Security Agreement, An Attorney in Fact is someone who is empowered to act on behalf of another individual (the “Principal”) in specific matters, which can range from financial management to business transactions, or other delegated responsibilities.

The significant aspect here is that anyone can be appointed as an Attorney in Fact—you don’t need to choose a licensed “Lawyer.” The powers of an Attorney in Fact are defined and limited by the scope of the legal document appointing them. They cannot represent the principal in court unless specific provisions allow them to do so.

Appointment of Attorney in Fact by Affidavit or Contract Security Agreement:

Beyond the traditional Power of Attorney, an Attorney in Fact can also be appointed via an Affidavit or a Contract Security Agreement**. This approach offers flexibility in delegating authority and can be particularly useful in more complex legal and financial scenarios. Here’s how the process works:

1. Appointment by Affidavit: A person (the principal) can issue an affidavit explicitly appointing someone as their Attorney in Fact. This sworn document gives the appointee the authority to act on the principal’s behalf in accordance with the scope outlined in the affidavit.

2. Appointment by Contract Security Agreement: In some cases, a Contract Security Agreement may be used to formalize the appointment of an Attorney in Fact. This contractual arrangement sets out the rights and responsibilities of both the principal and the appointee, ensuring that the agent’s powers are clearly defined and agreed upon.

In both cases, the appointed Attorney in Fact takes on the duties specified in the document but cannot act as a “Lawyer” or “Attorney at Law” unless otherwise permitted by statute or court order.

The Importance of Being Your Own Attorney in Fact:

Every private citizen is inherently expected to act as their own Attorney in Fact when handling their personal affairs. This principle emphasizes personal sovereignty—retaining control over one’s decisions, finances, and legal rights. Acting as your own Attorney in Fact ensures that you maintain full agency over your legal and financial decisions.

However, when you appoint another person as your Attorney in Fact, or when you retain a “Lawyer” to represent you, you are effectively delegating your power and authority to someone else. This transfer of power has significant consequences in the legal realm, particularly when retaining an “Attorney at Law.”

Consequences of Retaining a “Lawyer”: Becoming a Ward of the Court:

When an individual retains an “Attorney at Law,” they surrender a degree of control over their legal affairs. Under § 4 ATTORNEY & CLIENT 7 C.J.S. and §§ 2-3 ATTORNEY & CLIENT 7 C.J.S., the court views a represented client as a “ward of the court.” This means the client is no longer fully responsible for their own legal matters—their “attorney” assumes the role of guardian within the context of the legal system.

The implications are as follows:

– Surrender of Control: By hiring a “Lawyer,” the client effectively relinquishes their direct decision-making authority, trusting their “attorney” to act on their behalf.

– Court Supervision: Once an “Attorney at Law” is retained, the client is subject to the court’s authority, with the “attorney” primarily serving the court’s interests, which may not always align with the client’s desires.

– Loss of Personal Sovereignty: While many view hiring an “Attorney at Law” as an essential part of legal proceedings, it’s important to recognize that doing so results in the client becoming a “ward of the court,” meaning they are no longer considered fully capable of managing their own legal matters.

Furthermore, by becoming a “ward of the court,” individuals effectively grant jurisdiction to the respective court/administrative tribunal, which results in the loss of rights through the contractual relationship with their retained “attorney” or “handler.” This situation can usher individuals into the legal system, rendering them subject to its colorable laws and potential deprivation under the “color of law.”

3. What is a ward of the court?

“Wards of court. Infants and persons of unsound mind placed by the court under the care of a guardian. Davis Committee v. Loney, 290 Ky. 644, 162 S.W. 2d. 189, 190. Their rights must e guarded jealously. Montgomery v. Erie R. Co., C.C.A.N.J., 97 F, 2d 289, 292. See Guardianship”

4. What is “In Propria Persona”

particularly “…because if pleaded by an attorney…”

“In propria persona /in pröwpry! persówn!/. In one’s own proper person. It was formerly a rule in pleading that pleas to the jurisdiction of the court must be plead in propria persona, because if pleaded by attorney they admit the jurisdiction, as an attorney is an officer of the court, and he is presumed to plead after having obtained leave, which admits the jurisdiction. See Pro se.”

Conclusion: Maintaining Personal Sovereignty:

Understanding the difference between an “Attorney at Law” and an Attorney in Fact is vital for maintaining personal control over your affairs. By acting as your own Attorney in Fact, or appointing a trusted individual through an affidavit or Contract Security Agreement, you preserve your right to make decisions on your own behalf. However, retaining a “Lawyer” means delegating significant power and potentially becoming a “ward of the court,” subject to the judicial system’s supervision; “subject to the jurisdiction of…”

For those who value personal sovereignty and control, it is important to carefully consider how you approach legal representation and the appointment of others to act on your behalf. Whether acting independently as your own Attorney in Fact or appointing another, this decision holds significant weight in how your legal and financial matters are managed.