When it comes to protecting your personal or business assets, becoming a secured party under the Uniform Commercial Code (UCC) provides the legal framework to gain full control over your property. By filing the appropriate documentation, you ensure that your interests are legally recognized and protected from claims by third parties. Here’s how you can become a secured party in three essential steps:

1. Creating a Security Agreement

A security agreement is the foundation of becoming a secured party. This legally binding document outlines the terms under which the debtor (you, the owner of the assets) grants a security interest in specific property or collateral to a secured party (which may also be you in a dual capacity).

The security agreement clearly specifies:

– The property (collateral) being pledged

– The rights and duties of both the secured party and the debtor

– The conditions under which the secured party can claim the collateral, especially in case of default on a loan or obligation

This agreement is crucial because it creates a formal interest that is enforceable in court, ensuring that you have documented ownership and control over your assets.

2. Filing a UCC1 Financing Statement

The next step in becoming a secured party is filing a UCC1 Financing Statement. This filing is a public record that establishes your secured interest in the collateral, providing notice to the world that you have a claim to the assets listed in the security agreement.

– Purpose: The UCC1 serves as an official notice to other creditors, lenders, or third parties that the property listed in the document is secured by your interest.

– Details: The statement typically includes the debtor’s name, the secured party’s name, and a description of the collateral.

Filing the UCC1 gives you the status of a secured party, which ensures that your interests are legally recognized, especially if someone else tries to claim rights over the same property.

3. Amending with UCC3 for Future Collateral

As you acquire more assets, it’s important to amend your original UCC filing to ensure continued protection. A UCC3 Financing Statement Amendment is the legal form used to make changes to the original UCC1 filing.

– Adding Collateral: If you obtain new property or assets, you can update the original agreement to include this collateral.

– Removing or Modifying: You can also remove collateral or update terms, ensuring that your filings remain accurate and reflective of your assets.

The UCC3 amendment ensures that your secured interest extends to future collateral, giving you continued control over any new property you acquire.

Why Becoming a Secured Party Matters

As a secured party, you gain significant legal advantages:

– Priority in Claims: As the secured party, your claim to assets takes priority over other purported creditors.

– Protection Against Future Claims: Once your UCC1 is filed, it serves as legal notice to the public, protecting your assets from being claimed by others.

– Full Control Over Your Assets: By continuously updating your UCC filings, you ensure that your ownership and control over your property are recognized and enforceable. You have standing.

The importance of becoming a secured party cannot be overstated, especially in situations “purported” involving loans, auto loans, mortgages, utility bills, and credit cards—all of which are governed by the UCC. This legal framework ensures that you have standing and that your assets remain under your control and protected from outside claims.

By following these steps—creating a security agreement, filing a UCC1 Financing Statement, and using UCC3 amendments—you can solidify your position as the holder in due course, ensuring that your property remains secure and legally protected.

BECOME HOLDER IN DUE COURSE

-

Discharging Debt Through Equity Remedy: Vehicle, Mortgage, and Credit Relief

$10,000.00Original price was: $10,000.00.$6,000.00Current price is: $6,000.00. Add to cart -

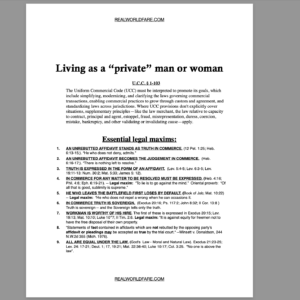

Status Correction: Living as a “Private” Man or Woman

$33.00 Add to cart -

GHOST Attorney/Writer Lawsuit, Pleading, Affidavit, Document Service: Automobiles, Foreclosures, Credit Cards, Quiet Title Actions, Slander of Title,

$5,000.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

Eliminate PURPORTED “Loan” on private Automobile, Recoup Assets, Payments, and ALL Money Paid

$3,600.00 Add to cart -

Secured Party/Creditor: Correct Status, Claim Estate, All Assets, Exemption, and Rights

Rated 5.00 out of 5$250,000.00Original price was: $250,000.00.$10,000.00Current price is: $10,000.00. Add to cart -

Private Bank(er) EIN (Employer Identification Number)

Rated 5.00 out of 5$333.00 Add to cart -

Estate EIN (Employer Identification Number)

$333.00Original price was: $333.00.$150.00Current price is: $150.00. Add to cart -

Private Foreign Non-Statutory Trust – A Secure, Sovereign Financial Solution

$6,000.00 Add to cart -

Credit Privacy Number (CPN)

Rated 5.00 out of 5$1,300.00 Add to cart