In the realm of financial obligations, there is a fundamental principle that separates the tangible from the intangible, the government-created from the individually created. This principle states that public debt, which is reflected in government-issued bonds, cannot be intermingled with private credit instruments. Essentially, what is owed publicly cannot be directly offset by private credit.

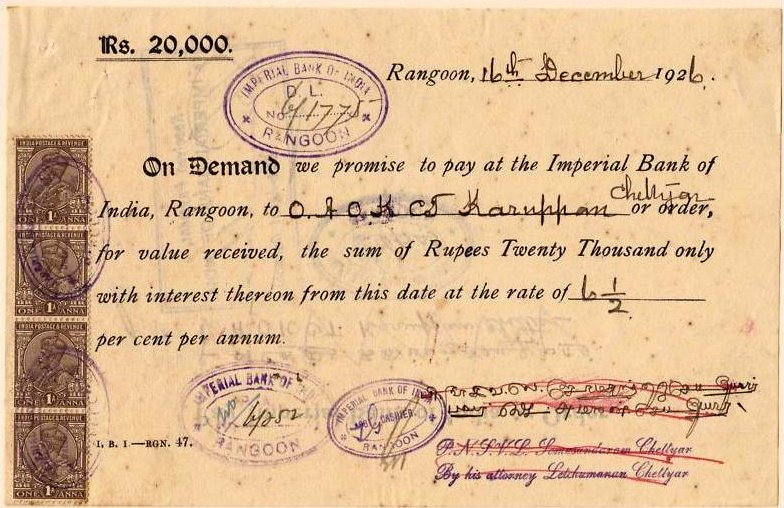

When an individual, acting as a private creditor, issues a bond, it signifies a public debt. This bond can be used to settle other public debts, but it must remain on the public side of the accounting ledger. Private instruments, such as personal promissory notes, should not use public identifiers like federal reserve routing numbers; instead, they should utilize private routing numbers associated with an individual’s Employer Identification Number (EIN) along with a closed account number.

This closed account number, once accepted and listed on a UCC-1 filing, transitions to the private side, earmarked for personal adjustment and setoff. This act of acceptance signifies that the individual has informed relevant authorities, like the Treasury, that the account is being used as collateral, thus establishing secured party rights.

See Related: “Understanding UCC Filings: The Impact on Business Assets and Credit“

The filing of a UCC-1 is not to claim these rights, which are inherently private, but rather to notify the public side of one’s secured position. This allows the individual to use their account for the adjustment and setoff of public debts. Interestingly, while actual currency does not exist on the private ledger, on the public side, debt is utilized as a currency substitute to discharge other public debts.

A poignant case in point is a letter acquired from a confidential source where an individual demands from their lender a cash receipt for a promissory note or a discharge of the outstanding balance. This right to claim stems from the factual assertion that the note itself holds value which has been monetized and should be accounted for, providing the individual with a right to reclaim it or its equivalent value, and proceeds from it.

a Promissory Note is actually a asset to the borrower with cash value given cash is just actually DEBT. THER IS NO MONEY.

In essence, the law maintains a clear separation between the roles of public entities and private individuals, especially in financial dealings. This separation ensures that the state, which operates in the public sphere, cannot lay direct claims against an individual, but may instead approach the ‘straw man’—a term used to describe the entity created by public registration, such as licenses or business registrations. The state’s interest lies not in the tangible assets registered to the ‘straw man’ but rather in the individual’s credit.

When the state faces a shortage, metaphorically needing ‘paperclips’ for its operations, it seeks out resources. Taxation, licenses, and fees are traditional means, but not always sufficient. Therefore, the state often turns to the individual’s credit, and if not willingly provided, may leverage the individual’s failure to comply—or ‘dishonor’—as a means to access it. This scenario underlines the importance of understanding the interplay between personal liability and public claims, emphasizing the need for individuals to recognize and assert their rights within this complex system.